‘There may not be a contention after all’ in extending universe banter

- Technology

- July 2, 2021

Our universe is growing, yet our two fundamental approaches to gauge how quick this extension is going on have brought about various answers. For as long as decade, astrophysicists have been steadily separating into two camps: one that accepts that the thing that matters is critical, and another that figures it very well may be because of blunders in estimation.

On the off chance that incidentally, blunders are causing the jumble, that would affirm our essential model of how the universe functions. The other chance presents a string that, when pulled, would propose some crucial missing new material science is expected to fasten it back together. For quite a long while, each new piece of proof from telescopes has wavered the contention to and fro, leading to what has been known as the ‘Hubble tension.’

Wendy Freedman, a famous stargazer and the John and Marion Sullivan University Professor in Astronomy and Astrophysics at the University of Chicago, made a portion of the first estimations of the development pace of the universe that brought about a higher worth of the Hubble steady. However, in another survey paper acknowledged to the Astrophysical Journal, Freedman gives an outline of the latest perceptions. Her decision: the most recent perceptions are starting to close the hole.

That is, there may not be a contention all things considered, and our standard model of the universe shouldn’t be fundamentally altered.

The rate at which the universe is growing is known as the Hubble steady, named for UChicago alum Edwin Hubble, SB 1910, Ph.D. 1917, who is credited with finding the extension of the universe in 1929. Researchers need to nail down this rate decisively, in light of the fact that the Hubble steady is attached to the age of the universe and how it developed after some time.

A generous wrinkle arose in the previous decade when results from the two principle estimation techniques started to veer. Yet, researchers are as yet discussing the meaning of the befuddle.

One approach to gauge the Hubble steady is by taking a gander at extremely faint light left over from the Big Bang, called the inestimable microwave foundation. This has been done both in space and on the ground with offices like the UChicago-drove South Pole Telescope. Researchers can take care of these perceptions into their ‘standard model’ of the early universe and run it forward on schedule to foresee what the Hubble consistent ought to be today; they find a solution of 67.4 kilometers each second per megaparsec.

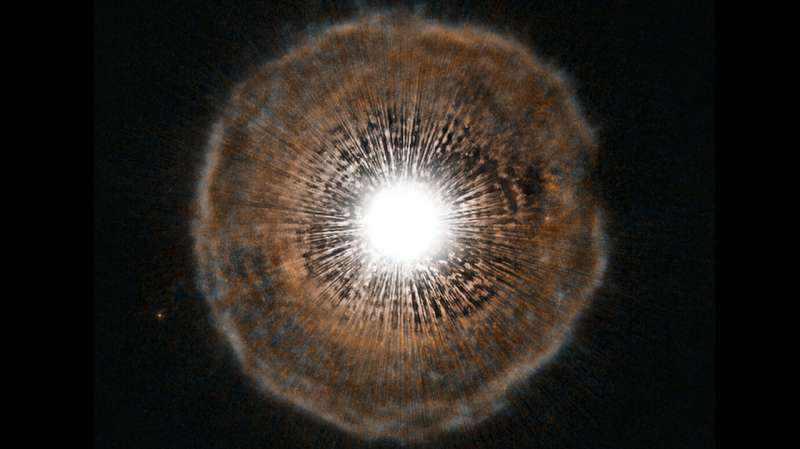

The other technique is to take a gander at stars and worlds in the close by universe, and measure their distances and how quick they are moving away from us. Freedman has been a main master on this strategy for a long time; in 2001, her group made one of the milestone estimations utilizing the Hubble Space Telescope to picture stars called Cepheids. The worth they found was 72. Freedman has kept on estimating Cepheids in the years since, investigating more telescope information each time; notwithstanding, in 2019, she and her associates distributed an answer dependent on a completely extraordinary strategy utilizing stars called red monsters. The thought was to cross-check the Cepheids with an autonomous technique.